The Simple Usefulness of the Secchi Disc | Science History Institute

“In 1865 Pope Pius IX decided he needed more accurate measurements of the turbidity of the Mediterranean Sea. His reasons were disputed even at the time—some sources say he wanted to measure water pollution in and around the Mediterranean; others that he wanted more reliable navigational charts; while still others maintained that he simply wanted written proof of the beauty and clarity of the sea’s waters. Whatever the reason, Pius IX wanted turbidity measurements standardized.”

Physics of Birds and Bees | Cosmos Magazine

It is thinkable that the investigation of the behaviour of migratory birds and carrier pigeons may some day lead to the understanding of some physical process which is not yet known.

Sincerely yours,

Albert Einstein.

When Science Breaks Bad | Arstechnica

Q. How would you go on an expedition to tropics in XVIII century?

A. “If you were an English naturalist in 1771 and you wanted to collect specimens from the tropics, you had to go on a slave ship; those were the only ships that went.

Darwin’s Children Drew All Over the On The Origin of Species Manuscript | The Appendix

’It’s all a great reminder that even legendary scientists had family lives, and that when we think about history, it’s important to remember that famous figures weren’t working in isolation. They were surrounded by far less famous friends, family members, acquaintances, and enemies. And sometimes, when we get lucky, we see some of their artifacts from the past too.‘’

Wasaburo Ooishi and the Jet Stream | Cosmos Magazine

“The jet stream is arguably the greatest weather system on Earth,” says Tim Woollings, a climate scientist in the Oxford University Department of Physics. “If you were only given one piece of information from which to infer something about the weather, then across much of the Earth’s surface you’d want it to be about the jet stream.”

Scientists for the People | AEON Magazine

“‘There are two types of popularisers,’ he wrote for a broad scientific audience in 1929. The first ‘feigns sympathy with the less educated’, but takes a condescending tone and ‘grows cranky’ without the ‘crutch’ of ‘jargon and ‘mathematical formulas’. The second takes ‘pleasure and pride’ in letting go of those crutches and succeeds in raising ‘the reader and himself into a more general sphere that lies above that of technical expertise’. If the first type of populariser was arrogant and paternalistic, the second displayed humility and respect for the non-scientist.”

A Lunar Pandemic | AEON Magazine

“Hard as it is to believe now, in the summer of 1969, millions across the US worried that the returning astronauts would spark a lunar pandemic on Earth. Nor did their fears lack merit. Scientists, bureaucrats and engineers across the federal government and the major universities of the US had spent years preparing for that possibility. It was one potential outcome of what they called ‘back contamination’: the introduction to Earth of alien microbes that could multiply exponentially in our benign biosphere.”

How Modern Mathematics Emerged From a Lost Islamic Library | BBC Future

“The House of Wisdom was destroyed in the Mongol Siege of Baghdad in 1258 (according to legend, so many manuscripts were tossed into the River Tigris that its waters turned black from ink), but the discoveries made there introduced a powerful, abstract mathematical language that would later be adopted by the Islamic empire, Europe, and ultimately, the entire world.”

Digging for Dorothea | The Royal Society Blog

“Her output reflects her passion, competence and innovative thinking as a paleontologist. Between 1903 and 1907 she published 15 papers on her Mediterranean excavations and the occurrence of dwarf species, in various journals – all had to be presented by Woodward. In total she published over 80 papers and reviews, becoming an established and well-respected member of the paleontological community.”

“Let us Calculate!” | Public Domain Review

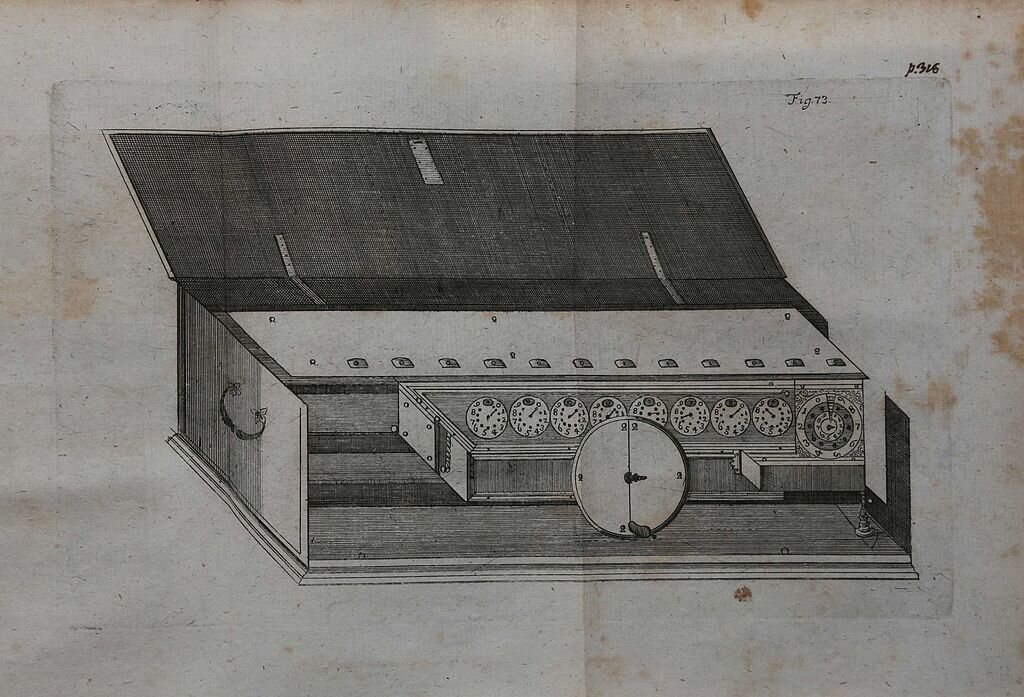

“There was a resurgence of interest in Leibniz’s role in the history of computation after workmen fixing a leaking roof discovered a mysterious machine discarded in the corner of an attic at the University of Göttingen in 1879. With its cylinders of polished brass and oaken handles, the artefact was identified as one of a number of early mechanical calculating devices that Leibniz invented in the late seventeenth century.”

Inside the Secret Math Society Known Simply as Nicolas Bourbaki | Quanta Magazine

“Bourbaki began in 1934, the initiative of a small number of recent ENS alumni. Many of them were among the best mathematicians of their generation. But as they surveyed their field, they saw a problem. The exact nature of that problem is also the subject of myth.”

The Classification of Humankind, and the Birth of Population Science | The MIT Press Reader

“While others made similar claims before him — Machiavelli, for example, asserted that population will expand until “the world will purge itself” through means of plagues or famines — Malthus’s pessimistic provocation provided fertile and innovative ground for later engineers, futurists, and optimists alike.”

When Math Gets Impossibly Hard | Quanta Magazine

“Mathematical impossibility is different. We begin with unambiguous assumptions and use mathematical reasoning and logic to conclude that some outcome is impossible. No amount of luck, persistence, time or skill will make the task possible. The history of mathematics is rich in proofs of impossibility. Many are among the most celebrated results in mathematics. But it was not always so.”

Galileo the Artist | Nature

“As a young man, Galileo Galilei considered becoming a painter.”

Alfred Wegener and the Continental Drift | COSMOS | Jeff Glorfeld

“Wegener expanded this “debunked” hypothesis in 1915 into what NASA calls “one of the most influential and controversial books in the history of science: The Origin of Continents and Oceans”.”

Claude Bernard | French Physiologist | 1813-1878

“Reasoning will always be correct when applied to accurate notions and precise facts; but it can lead only to error when the notions or facts on which it rests were originally tainted with error or inaccuracy. That is why experimentation, or the art of securing rigorous and well-defined experiments, is the practical basis and, in a way, the executive branch of the experimental method as applied to medicine.”

Sarah Frances Whiting and the “Photography of the Invisible” | Physics Today

““Near the end of her career, she reflected on “the somewhat nerve-wearing experience of constantly being in places where a woman was not expected to be, and doing what women did not conventionally do.”

On the Great and Terrible Hurricane of 1938 | Lit Hub

“Forecasts possess no intrinsic value. They acquire value through their ability to influence the decisions made by users of the forecasts”.

Allan H. Murphy, Wea. Forecasting (1993) 8 (2): 281–293.

Maria Ylagan Orosa and the Chemistry of Resistance | Lady Science

“As a humanitarian, she believed knowledge was something to share, not sell. “When you start an experiment, finish it and write the results for others to use,” she often told her assistants. Her erasure was completed by corporations, who commodified her scientific contributions without acknowledging their origins.”

Casimir Funk Introduced us to Vitamins | COSMOS Magazine

“A century later, although we may find limitations in Casimir’s theory, this does not detract from his genius, or his influence on medical thinking and his role in founding the vitamin industry.”